De minimis — which is short for the Latin maxim de minimis non curat lex: “the law cares not for small things” or “the law does not concern itself with trifles” — is a legal doctrine that refers to trivial matters that are not worthy of judicial scrutiny. In On Davis v. Gap, Inc., the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit pointed out that “the de minimis doctrine essentially provides that where unauthorized copying is sufficiently trivial, ‘the law will not impose legal consequences.’”[1] In other words, if you use an element of a copyrighted work without permission, and that element is de minimis, like say, a sample of a drum kick from an old Led Zeppelin song, then the use is not infringement. In noting the importance of locating when copying is actually “trivial,” the Second Circuit further noted that “[t]he de minimis doctrine is rarely discussed in copyright opinions because suits are rarely brought over trivial instances of copying. Nonetheless, it is an important aspect of the law of copyright.” In further describing the frequency in everyday life and the ordinary, practical nature of de minimis, the Second Circuit also added that:

Trivial copying is a significant part of modern life. Most honest citizens in the modern world frequently engage, without hesitation, in trivial copying that, but for the de minimis doctrine, would technically constitute a violation of law. We do not hesitate to make a photocopy of a letter from a friend to show to another friend, or of a favorite cartoon to post on the refrigerator. Parents in Central Park photograph their children perched on Jose de Creeft’s Alice in Wonderland sculpture. We record television programs aired while we are out, so as to watch them at a more convenient hour. 8 Waiters at a restaurant sing “Happy Birthday” at a patron’s table. When we do such things, it is not that we are breaking the law but unlikely to be sued given the high cost of litigation. Because of the de minimis doctrine, in trivial instances of copying, we are in fact not breaking the law. If a copyright owner were to sue the makers of trivial copies, judgment would be for the defendants. The case would be dismissed because trivial copying is not an infringement.[2]

As a broad principle well recognized in common law,[3] de minimis is understood to mean usage that does not amount to actionable (unlawful) copying under the law. “Under the de minimis doctrine, some things, while technically violations of the law, are considered too petty to waste the time and resources of the court.”[4] In the context of a copyright infringement lawsuit, if the allegedly infringing work makes such a quantitatively insubstantial use of the copyrighted work as to fall below the threshold required for actionable copying, courts reject the claim on that basis and find no infringement. So whether the allegedly infringing use is de minimis is also a consideration of the substantial similarity analysis. Thus, in a context of sampling sound recordings, the de minimis threshold is the level at which courts deem the appropriation of a sound recording to be “trivial” and “quantitatively insubstantial” and therefore not an infringement. Think of something like a sample of a kick drum, a bass-stab, or two short notes from a long melodic phrase, and the like.[5]

De minimis is particularly important to understand prior to the scope of fair use, because if a sample is de minimis, then there’s no need to for the courts to engage in the fair use test. “The fair use defense involves a careful examination of many factors, often confronting courts with a perplexing task. If the allegedly infringing work makes such a quantitatively insubstantial use of the copyrighted work as to fall below the threshold required for actionable copying, it makes more sense to reject the claim on that basis and find no infringement, rather than undertake an elaborate fair use analysis in order to uphold a defense.”[6] In this way, the de minimis doctrine recognizes that there are instances in which an appropriation (like a sample from a sound recording or words from a book) is too small, too trivial to be considered copyright infringement. Although sampling case law has addressed this issue, most notably in Newton v. Diamond, there is, however, no arbitrary de minimis threshold. In fact, what occurred in Newton v. Diamond, according to Dr. Lawrence Ferrera, is very insightful in this regard:

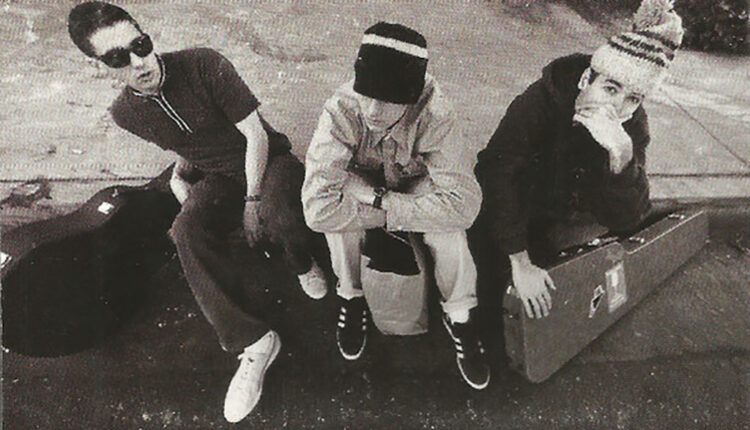

I was the musicologist for the defendant, the Beastie Boys and all of the co-defendants. And in that case, James Newton…had sold the sound recording rights to his song, the 1978 song “Choir.” He sold the rights to the sound recording, but he held on to the publishing rights to the composition. The Beastie Boys took the first 5 and a half seconds, which is three notes, which is essentially James Newton in a falsetto singing these notes [begins to play the notes, then sings the notes].

And simultaneous with singing those three notes, he over blows the flute, same time, and he creates a multi-phonic, which is [he plays], which is just literally a multi-phonic of sounds. And so, essentially, it was three notes, and he actually even had a score, that actually accompanied that in his 1978 filing for copyright. The Beastie Boys duly licensed from the record company, that Newton sold his rights to (I think they were in Germany), the use of that sound recording sample. But they didn’t take the license on the three notes. He [Newton] sued. I was the musicologist.

And as I presented, I said, “Those three notes, first of all, they’re de minimis. Because you only hear it once in this 4-and-a-half-minute work. You never hear it again. And the de minimis test or analysis is, what is the substantiality of the portion at issue within the context of the whole song, not the new song, the original song. That the Beastie Boys looped that [sample], something like 47 times, in their song “Pass the Mic” is not the de minimis test. It’s how substantial was that three notes in the original Newton work. And the point was that it was de minimis. It was minimal…. So I established that, first of all, there’s nothing new about what he did. Moreover, those three notes, I gave oodles of examples in major works where that was actually a motif. And so I had some really great prior, what is called prior art, as well as you know, everything else. And Judge Menella, of the District Court in Los Angeles, on the basis on everything, not just what I wrote but what the defendants proffered, dismissed the case. It was appealed. The 9th Circuit upheld, but with one dissent. And then it went to the en banc. I don’t know how many judges looked at it, I think nine or ten or whatever in the 9th Circuit, and they unanimously upheld on the de minimis.

So, there is a case where if there’s three notes in the composition — So I’ve done the analysis and say, “Hey, you know what, yeah, maybe they did copy those three notes.” [laughs] The point is, it doesn’t matter. Because it’s de minimis. And in the case of Newton, they did copy it. Because they sampled it. And they licensed the sample. So there’s no question that they copied it. But the copying, the copied expression was not sufficiently substantial for there to be, and this is important, musicological support for a claim of copyright infringement.[7]

Newton v. Diamond aside, the circumstances of each sample are different. Therefore, in the courts, de minimis is determined on a case-by-case basis. For this reason, the notion of a default or precise de minimis sample line of one, two, or three notes, or one, two, or three seconds is misleading. There is no “bright line” de minimis threshold for what constitutes a de minimis sample of a sound recording.

Since de minimis is a less complicated concept to comprehend, I will leave the description of it where it is and I’ll just make one final point. All copyrightable subject matter, from sound recordings to literary works to motion pictures — is subject to a de minimis threshold for infringement.

Notes:

1. On Davis v. Gap, Inc., 246 F.3d 152 (2nd Cir. 2001) (citations omitted) (emphasis mine).

2. Id. (emphasis mine).

3. Common law (also known as case law or precedent) is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action.[1] A “common law system” is a legal system that gives great precedential weight to common law,[2] on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different occasions.[3] —http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_law.

4. Jennifer R. R. Mueller, “All Mixed Up: Bridgeport Music v. Dimension Films and De Minimis Digital Sampling,” Indiana Law Journal, Vol. 81, Issue 1, Article 22 (2006), 435 (emphasis mine).

5. For a good example of a court’s description of the de minimis doctrine, see Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc., 126 F. 3d 70 – Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit (1997).

6. Id.

7. Amir Said interview with Dr. Lawrence Ferrara, November 29, 2018.